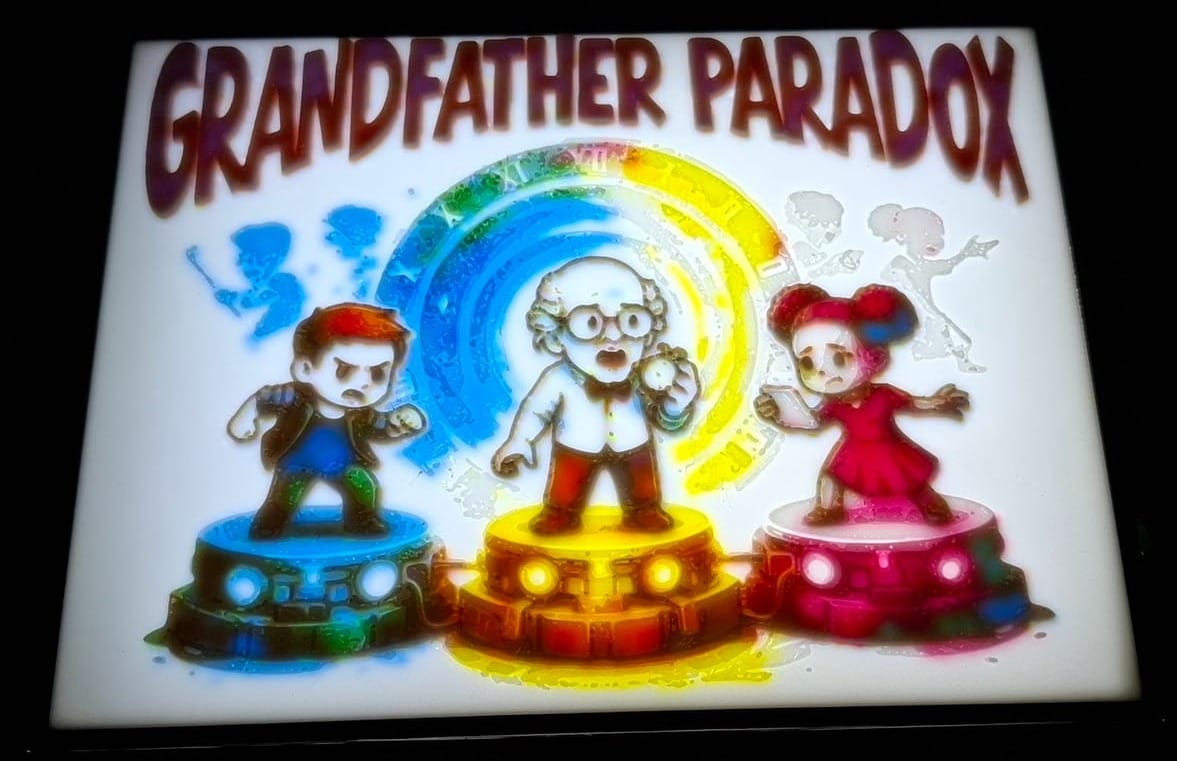

Grandfather Paradox

The original game was called Let's Kill Hitler.

The concept was a kind of reverse Cluedo with time travel. Instead of figuring out who did the murder, everyone's trying to do it, and the problem you're solving is how to make sure your version of events is the only one that sticks. It was also, honestly, edgy for the sake of edginess. The kind of title that puts off more players than it attracts, and the underlying concept was genuinely hard to transform into a working mechanic.

So the title went. The time travel and murder concepts stayed.

Let's Kill Hitler became Let's Kill Grandpa, which eventually became Grandfather Paradox. The justifications for why you'd want to kill (or save) your grandfather got progressively thinner and harder to work out until I dropped them entirely. Someone has to kill Grandfather Paradox. Someone else has to save him. It doesn't really need an explanation. Both jobs fall to you and your time clones.

The thing that carried over from the original idea was the pre-programming. Your past versions are locked into the actions you gave them - they can't adapt, they can't react, they just keep doing what you told them to do. What you can change is the framework those actions happen in. Move the time machines. Change where the Grandfather Paradox time clones go. Grab the weapons out of the hands of your previous self. Set things up so your loop one echo blunders into exactly the right place at exactly the right moment, even though it has no idea that's what it's doing other than following its predestined path.

By loop three there are three versions of you on the board, three versions of Grandfather Paradox, and a board full of past decisions you can't take back.

The first playtest was four players, about ninety minutes, a fair amount of re-explaining. Some players immediately grasped the "set up earlier characters to make things work for later ones" idea and started playing across all three loops from turn one. Others played more within each loop, treating it almost as three separate games. Both approaches worked, which felt like a good sign - the game has layers but doesn't require you to use all of them immediately.

What it actually feels like to play is a headache. A good headache, but a headache. The players who do well are usually the ones who learn to let go of optimisation and embrace the chaos instead. There's no clean solution. There's just the mess you made in a previous loop, and whether you can make it work for you.

There are still things to sort before Cannes - the end-game bonus scoring needs proper testing rather than theorising, and I want to make sure the weapon spawning creates the right kind of scarcity. But the Nuits d'Off is specifically for prototypes, and presenting something unfinished that needs real play is exactly what it's for.

So I'm looking forward to finding out what works.

Grandfather Paradox is a time-loop programming game for 3–6 players. It will be at the Nuits d'Off at the Festival de Jeux in Cannes. If you're going and want a game, find me there.